Awaiting the Next Crisis

Disclosure: We are reader-supported. If you purchase from a link on our site, we may earn a commission. Learn more

Last Updated on: 17th November 2016, 07:01 pm

It's been said that the responses to a crisis sow the seeds of the next upheaval. Indeed, history suggests that the so-called fixes often fall short of expectations. First, they fail to take account of the fact that the causes of each episode are often unique. Second, they give short shrift to the reality that government policymaking has unintended consequences. While it is hard to know for sure how the measures that were introduced in the wake of the global financial crisis will pan out, it is possible to identify vulnerabilities and areas of concern.

The most troubling, perhaps, is the widespread embrace of risky investments and strategies. Up until recently, the Federal Reserve and other central banks made it clear that one goal of post-crisis policy was to increase risk-taking. In that sense, they have been wildly successful. Individuals and institutions alike have been reaching for return to an extraordinary degree, while Main Street and Wall Street have been happy to oblige. Equity valuations are at nosebleed levels, spreads on the obligations of even the least creditworthy borrowers have been compressed to unrealistic extremes, and there has been an unprecedented interest in owning illiquid securities and hard-to-value investments.

Misplaced faith?

Another threat to stability stems from potential missteps by policymakers. Over the past seven years (and in some cases, long before that), central bankers, in particular, have had the view that they needed to be very transparent and clear about their intentions. Investors, in turn, have become complacent about the threat of something going wrong. They have been willing to hold high-risk positions while downplaying the need for prudence or portfolio protection because of their faith that the Fed (and others) had their backs.

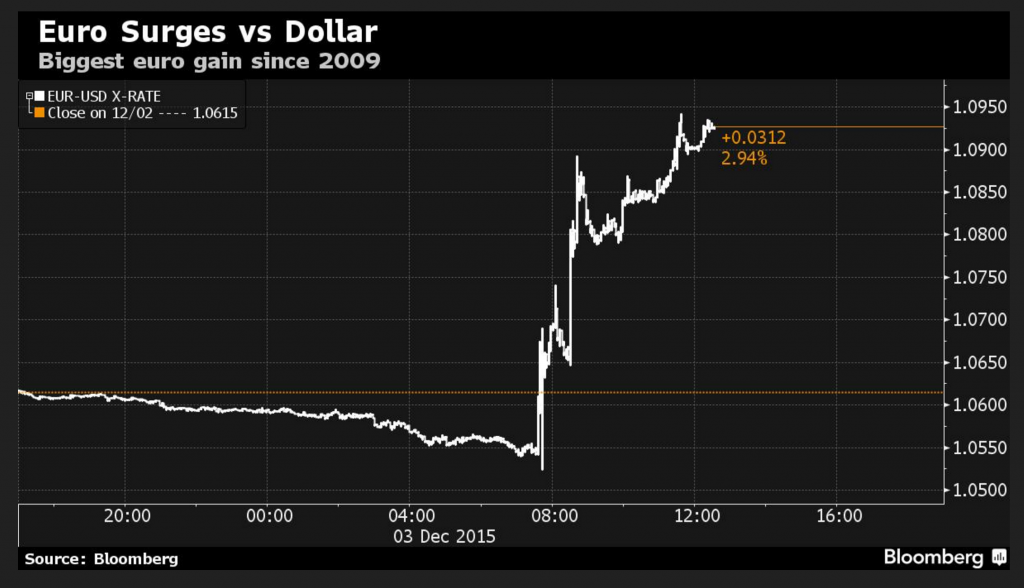

However, the assumption that central bankers know the correct course of action, and that they can articulate their views in a timely and coherent manner, could prove perilous. As was the case in early December, when currency (and other) markets erupted violently in response to the suggestion from European Central Bank President Mario Draghi that ECB policy might not be as accommodative as many had hoped, it doesn't take much nowadays to set off a trading firestorm.

The risks of overcrowding

That short-term reversal of fortunes also called to mind another consequence of post-crisis-era policies: the broad rush to own certain investments or deploy similar strategies. While “overcrowding” is occasionally hard to pinpoint–it is somewhat dependent on market and macroeconomic conditions, risk appetites, short and long-term supply and demand dynamics, and other variables–the basic idea is that it reflects a situation where even small changes in perceptions can trigger volatility spikes or violent reversals.

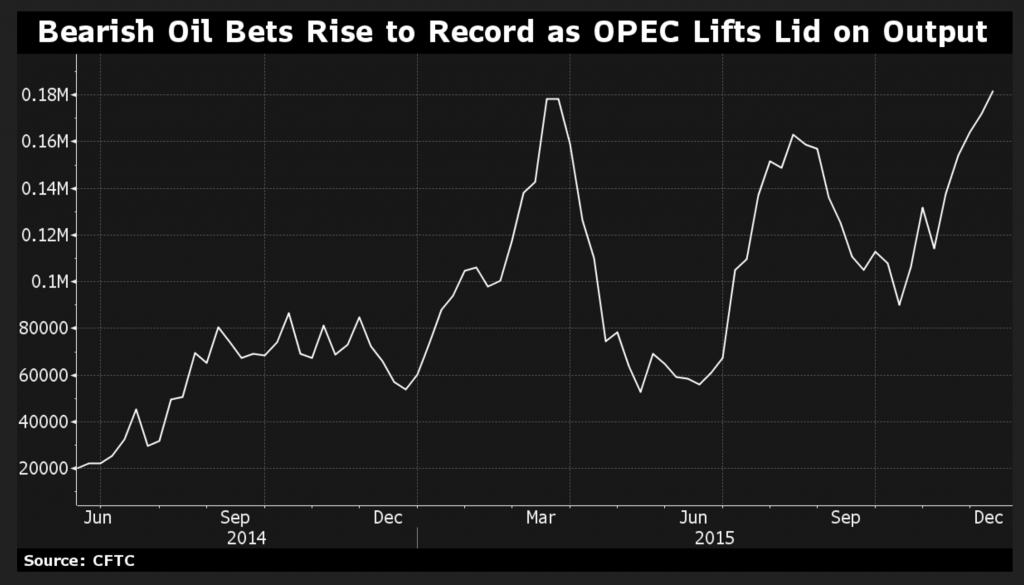

In fact, a variety of markets are seeing lop-sided positioning. Data from futures markets and surveys by prime brokers, as well as anecdotal reports, suggest that many are betting, for example, on a higher dollar and lower energy prices. While there are reasons to believe, as I argued in “U.S. Dollar: Last Currency Standing,” that the longer-term outlook for the U.S. currency remains positive, there is a risk that even a mildly disappointing economic data point could see some investors heading for the exits amid concerns that the Fed may be forced to reverse course and become accommodative again.

In regard to oil (and other commodities), there's little doubt that bearish forces remain at work. Saudi Arabia looks to be playing the long game as it floods the market in an attempt to eliminate competition from U.S. shale oil producers. More broadly, a strong dollar and slowing growth in China (and elsewhere) are undermining demand for energy. At the same time, high debt levels, softer economic conditions, and capital repatriation by skittish foreign investors is spurring many oil producers to pump out as much as they can, despite falling prices and burgeoning supplies.

Destabilizing knock-on effects

Still, it is not hard to imagine that a sudden change of heart by the Saudis, a pronounced wave of bankruptcies among producers, or a military flare-up in the Middle East might lead to panic short-covering and market upheaval that leaves some participants in serious trouble. The same could also be said with respect to other beaten-down commodities (as well as the high-flying dollar). Even if the disruption proves temporary, it could have destabilizing knock-on effects.

Regulatory initiatives have also brought about changes in market structure that could exacerbate future upheaval. The first is the “Volker Rule,” which I discussed in “Anything But Positive for Bond Markets.” While it is designed to ensure that banks don't engage in the kinds of speculative activities that led to the 2008 meltdown, it has also fostered something else: illiquid trading conditions. Because commercial and investment banks are less willing or able to carry inventory that can facilitate short-term supply-and-demand imbalances, air pockets are more commonplace–and markets are more prone to sudden bouts of volatility and turbulence.

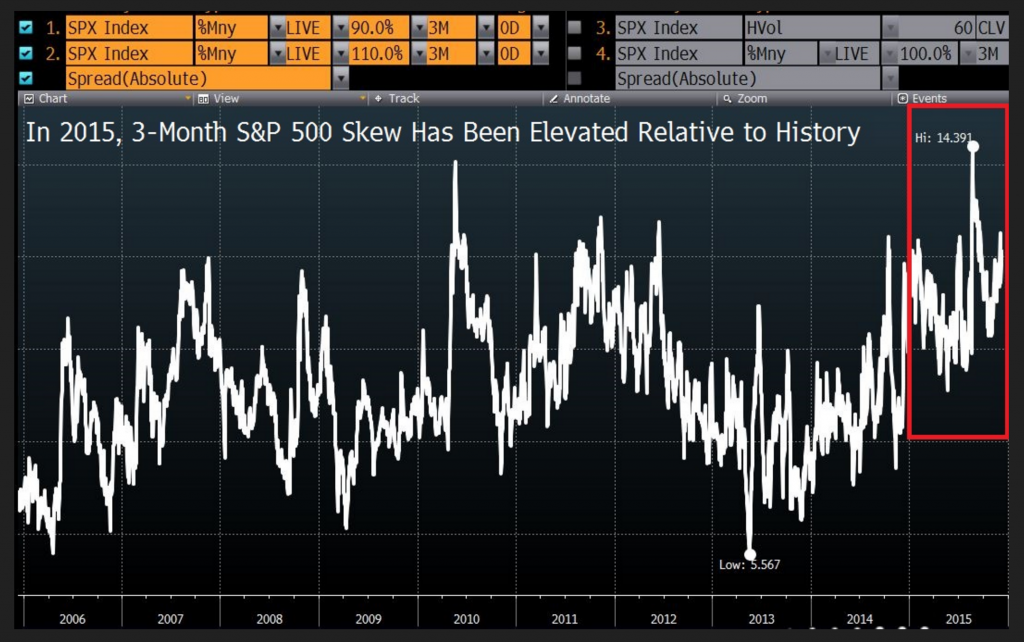

Another development that could cause problems down the road stems from well-intentioned efforts to ensure that systemically important financial institutions can weather another crisis. According to research by Deutsche Bank, detailed by Bloomberg, banks that are subject to stress test evaluations by federal regulators have apparently been “hoarding” equity-related put options in an effort to show their trading units can handle market shocks and pay out capital to shareholders. While this may work out as planned for them, others could suffer the consequences.

It goes with saying, of course, that it is hard to know if any of these various factors will be among those that feature most prominently during the next disaster, or whether there will be others, as yet unknown, that will turn things sour. Either way, when it comes to assessing risks, history does suggest one thing: the more you know, the better.

Silver

Silver Gold

Gold Platinum

Platinum Palladium

Palladium Bitcoin

Bitcoin Ethereum

Ethereum

Gold: $3,643.22

Gold: $3,643.22

Silver: $42.19

Silver: $42.19

Platinum: $1,400.17

Platinum: $1,400.17

Palladium: $1,211.59

Palladium: $1,211.59

Bitcoin: $115,947.70

Bitcoin: $115,947.70

Ethereum: $4,665.23

Ethereum: $4,665.23