- GOLD IRA

- Download Our 2024 Precious Metals IRA Investor’s Guide.

Click Here  Gold IRA

Gold IRA

Investing

Investing

-

- CRYPTO IRA

- PRICES & STATS

- RETIREMENT PLANS

- BLOG

Questions? Call (888) 820 1042

Questions? Call (888) 820 1042

China May Be About to Learn the Consequences of Excessive Debt Loads

Disclosure: Our content does not constitute financial advice. Speak to your financial advisor. We may earn money from companies reviewed. Learn more

There was a time when you might well have asked who cares if China’s debt load is excessive? But things have changed so much; China is now the second largest single economy in the world. As we saw last summer and at the beginning of this year; economic worries in China spill over to the rest of the world, USA included. The stock markets were rattled in August last year and at the beginning of this year when the S&P 500 lost 2.12% in one day on the back of a rout in the Chinese stock market.

Correlation between high private debt and financial crises

The Chinese Government has one of the lowest debt ratios of any type of economy at only 41% of GDP. However, private debt tells a different story, the private sector has run up a debt ratio of 205% of GDP. This debt burden began to expand rapidly in 2008 in the wake of the ongoing financial crisis which was causing the Chinese economy to slow down sharply.

The Chinese government began expanding loans to corporates in an attempt to increase national demand and encourage spending. Chinese companies took the prompt eagerly, and private debt has risen 76.7%. A high private debt ratio alone may not be enough to spark a recession or a financial crisis. However, it is one factor that is repetitive in many occasions of market stress and financial turmoil.

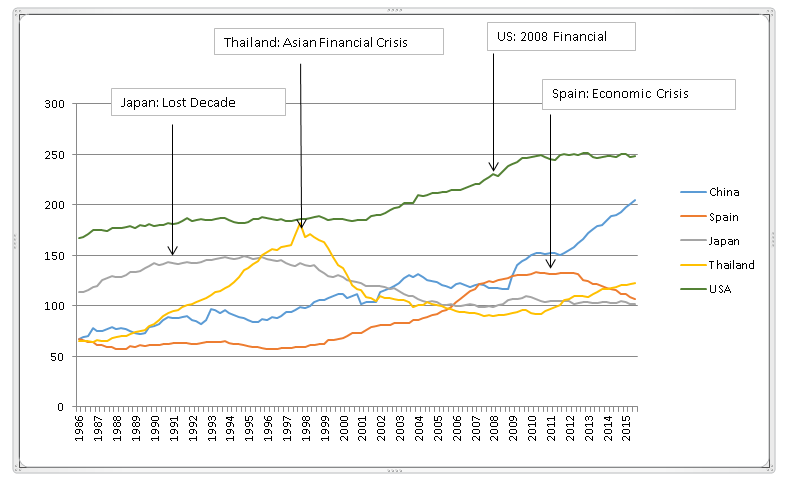

The chart above shows Non-Financial Private Sector Debt to National GDP for a number of countries, which all experienced financial distress when this ratio was relatively high. We can see how this ratio nearly peaked out at the beginning of the financial crisis in Japan, which led to the “Lost Decades”. The start of that crisis was due to a series of bad loans that crippled the Japanese banking system as soon as the asset bubble bust.

The financial woes that afflicted South East Asia in the late 90s, and in particular the run on the Thai Baht, also saw a comparatively high level of this ratio. In 1986 in Thailand the private debt to GDP ratio was 65.6% by 1997 it had almost tripled to 181.9%. The economic crisis in Spain in 2011 which also affected its financial markets saw the country narrowly escape default. The countries private debt ratio had risen from levels below 75% for most of the 90s to 131% at the onset of the crisis in 2011.

Something similar happened in the US, this ratio had been below 190% up until 2001; the tech bubble that followed also led the way to a sharp increase in private debt. By the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 private debt had reached 230% of GDP. The increase continued but in 2010, it settled just below 250%, a level it has been hovering around since.

The situation in China

China doesn’t seem to be looking to slow the expansion of private loans anytime soon either. In January this year, Chinese banks have already issued $385 billion, almost 3.5% of GDP, in new loans. Credit expansion doesn’t stop there; on February 29, The Peoples Bank of China reduced the amount of cash banks must keep on reserve, this policy freed another $100 billion approximately on bank’s balance sheets. This credit growth, however, comes at a time of concern. In December 2014, non-performing loans represented 1.2% of GDP a year later that figure had raised to 1.9% of GDP. Chinese officials reported that the total number of non-performing loans (NPL) had doubled from 2014 to 2015. That wouldn’t surprise after NPLs increased in number during 10 consecutive quarters.

The National Bureau of Economic Research issued a report on financial crises in 2010, which tracks the economic history of 14 developed countries spanning data over the past 140 years. The report identifies 5 episodes of global financial turmoil and shows that credit growth and low interest rates are associated with global financial crises. The report also makes the statement that “credit growth emerges as the single best predictor of financial instability.”

Consequences of Chinese Credit growth

China’s situation may be helped by the fact that it has a much lower Government debt to GDP ratio than any of the countries mentioned above at the time of their financial crisis, or even now. The government only has 41% of national debt to GDP, considerably low, leaving it plenty of room to be able to prop up its banking system if there were to be a crisis. The country also has relatively large foreign exchange reserves at $3.2 trillion and a current account surplus which can help defend in the case of capital departure. Yet it still has to be seen for how long consumers and corporates can keep taking out new loans before being completely unable to even service their debt.

Silver

Silver Gold

Gold Platinum

Platinum Palladium

Palladium Bitcoin

Bitcoin Ethereum

Ethereum

Gold: $2,387.15

Gold: $2,387.15

Silver: $27.92

Silver: $27.92

Platinum: $931.02

Platinum: $931.02

Palladium: $903.43

Palladium: $903.43

Bitcoin: $67,910.26

Bitcoin: $67,910.26

Ethereum: $3,278.81

Ethereum: $3,278.81